The New York City Waterfall Project was closed Oct. 13 2008 and the waterfalls have been removed. This page will remain up as a reference to this exciting art project.

What are the New York City Waterfalls?

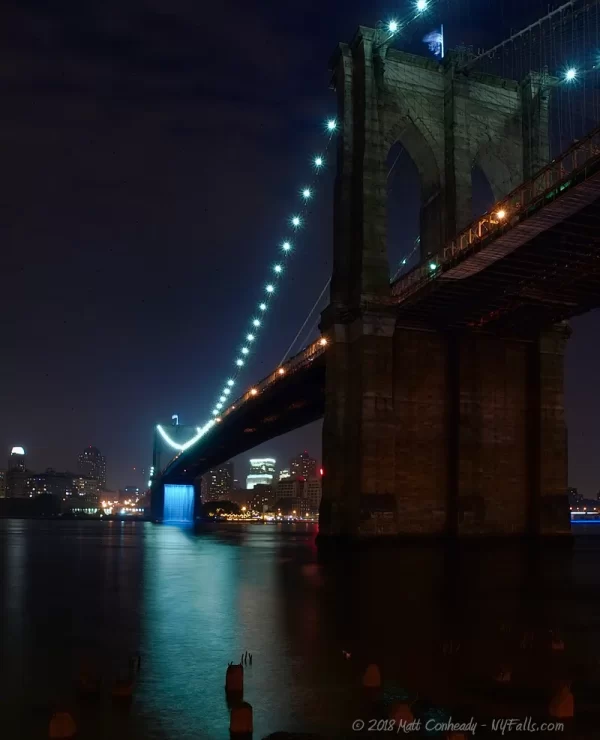

New York City hosted an exciting art exhibit featuring spectacular man-made waterfalls 90 to 120 feet (27 to 37 meters). They were softly lit at night and available for everyone to see. There were 4 waterfalls in total.

The New York City Waterfalls were constructed using building elements that are ubiquitous throughout New York: scaffolding was the backbone of the structures, and pumps brought water from the East River to the top; the water then fell from heights of 90 to 120 feet back into the river. Fish and aquatic life were protected by filtering the water through intake pools suspended in the river. To build the Waterfalls, Public Art Fund partnered with Tishman Construction Corporation and engaged a team of design, engineering and construction professionals.

The New York City Waterfalls were visible by land and boat, and because of their proximity to one another, viewers could see multiple waterfalls from various vantage points in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Governors Island. Dedicated boat journeys to view the Waterfalls, organized by the Public Art Fund in partnership with Circle Line Downtown, left from Pier 16 in Manhattan and provided up-close views of the installations. The Circle Line provided free and discounted trips daily for the public. Download the brochure.

Where was it?

The East River and New York Harbor hosted the waterfall project in the summer of 2008. The locations were:

Under the Brooklyn Bridge (on the Brooklyn Anchorage on the Brooklyn side, facing Manhattan)

Between Brooklyn’s piers 4 and 5 (west of the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, facing Manhattan)

Pier 35 in Manhattan (adjacent to South Street at Rutgers Street -north of the Manhattan Bridge, facing the Bridge)

Governors Island (on the north shore, facing Manhattan)

Interactive Map of the NYC Waterfalls (2008)

When was it?

Thursday, June 26th through Monday October 13th, 2008

The hours the waterfalls were running have been cut to reduce the impact on surrounding plants and trees. Turns out that spraying salt water into the air tends to kill things. Oops!

The hours of operation were Tuesdays and Thursdays through Sunday from 12:30 pm. to 9 p.m., and Mondays and Wednesdays from 5.30 p.m. to 9 p.m., through the scheduled end of the exhibition on Oct. 13.”

Who created these waterfalls?

The project was the brainchild of Danish artist Olafur Eliasson. Eliasson is considered one of his generation’s most influential artists. Throughout his career, he has taken inspiration from natural elements and phenomena, such as light, wind, fog, and water, to create sculptures and installations that evoke sensory experiences. He is perhaps best known for The weather project(2003) at Tate Modern in London, a giant sun made of 200 yellow lamps, mirrors and mist that transformed the museum’s massive Turbine Hall and drew over 2 million visitors during its five-month installation.

Olafur Eliasson was born in Copenhagen in 1967, and grew up in both Iceland and Denmark. He attended the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and currently divides his time between his family home in Copenhagen and his studio in Berlin. Studio Olafur Eliasson is a laboratory for spatial research that employs a team of 30 architects, engineers, craftsmen, and assistants who work together to conceptualize, test, engineer, and construct installations, sculptures, large-scale projects, and commissions. Recent works reflect Eliasson’s increased interest in architecture and the built environment. Since the mid-1990s, he has presented his work in numerous exhibitions and outdoor venues, and his work is currently on view in a major mid-career retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art through February 24, 2008, which will be expanded at The Museum of Modern Art and PS 1 Contemporary Art Center in New York opening on April 20, 2008.

“One of Eliasson’s great strengths as an artist is his ability to captivate viewers, which he will do by integrating the spectacular beauty of nature into the urban landscape on a dramatic scale,” said Steiner, curator of The New York City Waterfalls. Eliasson’s work often involves industrial materials that, when brought together, create dramatic installations that are as beautiful as they are unexpected.

“In developing The New York City Waterfalls, I have tried to work with today’s complex notion of public spaces,” said Eliasson. “The Waterfalls appear in the midst of the dense social, environmental, and political tissue that makes up the heart of New York City. They will give people the possibility to reconsider their relationships to the spectacular surroundings, and I hope to evoke experiences that are both individual and enhance a sense of collectivity.”

Why was this done?

The New York City Waterfalls provided an opportunity to highlight and celebrate the dramatic revitalization of the city’s waterfront. In recent years, the city has launched a number of key initiatives to open the waterfront for public use, including several significant capital projects, such as the creation of the Harbor District and the development of Brooklyn Bridge Park, Governors Island, and the East River Waterfront promenade in Lower Manhattan. In addition, as part of PlaNYC, the city has committed to open 90% of New York City’s waterways for recreation by reducing water pollution.

The bottom line is tourism dollars. The city expected tourism revenues to increase by $55 million due to this $15 million exhibition. In the end it was difficult to benchmark, whether the art installation may have worked…or tourism just ended up being high in 2008 anyway.

A “Green” Project

The Waterfalls were designed to be sensitive to the environment. The structures were not only supposed to protect fish, aquatic life, the river and the shoreline, but also ran on “green power”- electricity generated from renewable resources-for its operations. Public Art Fund worked with Constellation NewEnergy to provide the green energy for the project.

Turns out that it wasn’t so “Green.” Because of the installation’s light water flow, the wind picked up the falling water and sprayed it all over shore, drenching predestination paths, lawns, and trees with dirty salt water from the harbor. Several valuable landscaping trees were damaged or died. The project’s hours were cut after numerous complaints.

Public Response to the Waterfall Project

Dec 21, 2008 – NYC: “Waterfall projects has been declared a success”

I highly doubt this information is accurate. We have heard nothing but bad feedback from those that have seen the project, and those that were excited about it almost immediately lost that excitement after the taps were turned on and photos and video showed how disappointing they ended up, not to mention the hours of operation being drastically cut. When we were there, we found most people who were observing the art display were either residents of the city, or visiting the area for other reasons. Our conclusion: the increase in tourism and spending reported was not due to the waterfalls, but due to other tourism draws to the city, such as the final baseball seasons at Yankee and Shea Stadiums. Increases in traffic and spending in the region surrounding the display was most likely a majority of NYC residents viewing the curiosity rather than tourists from outside the region. We agree that an estimated 1.4 million people visited the NYC waterfalls , we just don’t think many of them came from outside the NYC region to do so – and that’s the true measure of success for these types of projects. Should the city continue to divert resources towards temporary projects such as these? Most people we have talked to say “no.”

August 30, 2008 – NYC Cuts Hours after Flood of Complaints

What happened?

Saltwater from the harbor was being lifted up into the air by a fine mist created by the waterfalls. The salty mist landed on nearby trees and plants. The water evaporated and the salt crystals remained, hindering photosynthesis, and slowly killing the plants. In response, the city acknowledged the problem and responded by reducing the number of operating hours from 101 to 49.5 hours per week.

The official statement

“Public Art Fund is proud to have commissioned ‘The New York City Waterfalls’ by Olafur Eliasson and to be presenting the project in collaboration with the city of New York. We believe it is an important work of art and it gives everyone the opportunity to experience the city and consider our surroundings in a different way. Since the opening, hundreds of thousands of people have seen the waterfalls by boat, by bike and walking along the shores.

“While an environmental assessment study was conducted prior to the project and measures were taken to ensure the safety of the surrounding landscapes, salt water mist off the river has affected several adjacent plantings. From the beginning of the project, an anemometer (wind meter) has been installed at each site, which shuts each waterfall off in the case of sustained winds that may blow saltwater onto the surrounding areas. In addition, when the saltwater mist damage was discovered, Public Art Fund immediately addressed the matter and began treating affected plant life. Expert arborists from the City Parks Department recommended a maintenance plan that includes washing tree leaves and flushing salt from tree roots daily, which was promptly undertaken and is being continued. While salt water can cause leaves to discolor or fall off prematurely, Parks has advised that with proper care any potential adverse effects can be limited. Public Art Fund and the Parks Department will continue to monitor the condition of the affected trees.

“Based on an updated recommendation of the Parks Department, we are reducing the hours of operation of “The New York City Waterfalls” beginning Monday, Sept. 8, from 101 hours per week to 49.5 hours per week in a further effort to stem the impact on the trees. The hours of operation will be Tuesdays and Thursdays through Sunday from 12:30 pm. to 9 p.m., and Mondays and Wednesdays from 5.30 p.m. to 9 p.m., through the scheduled end of the exhibition on Oct. 13.”